Ideas from the Speakers

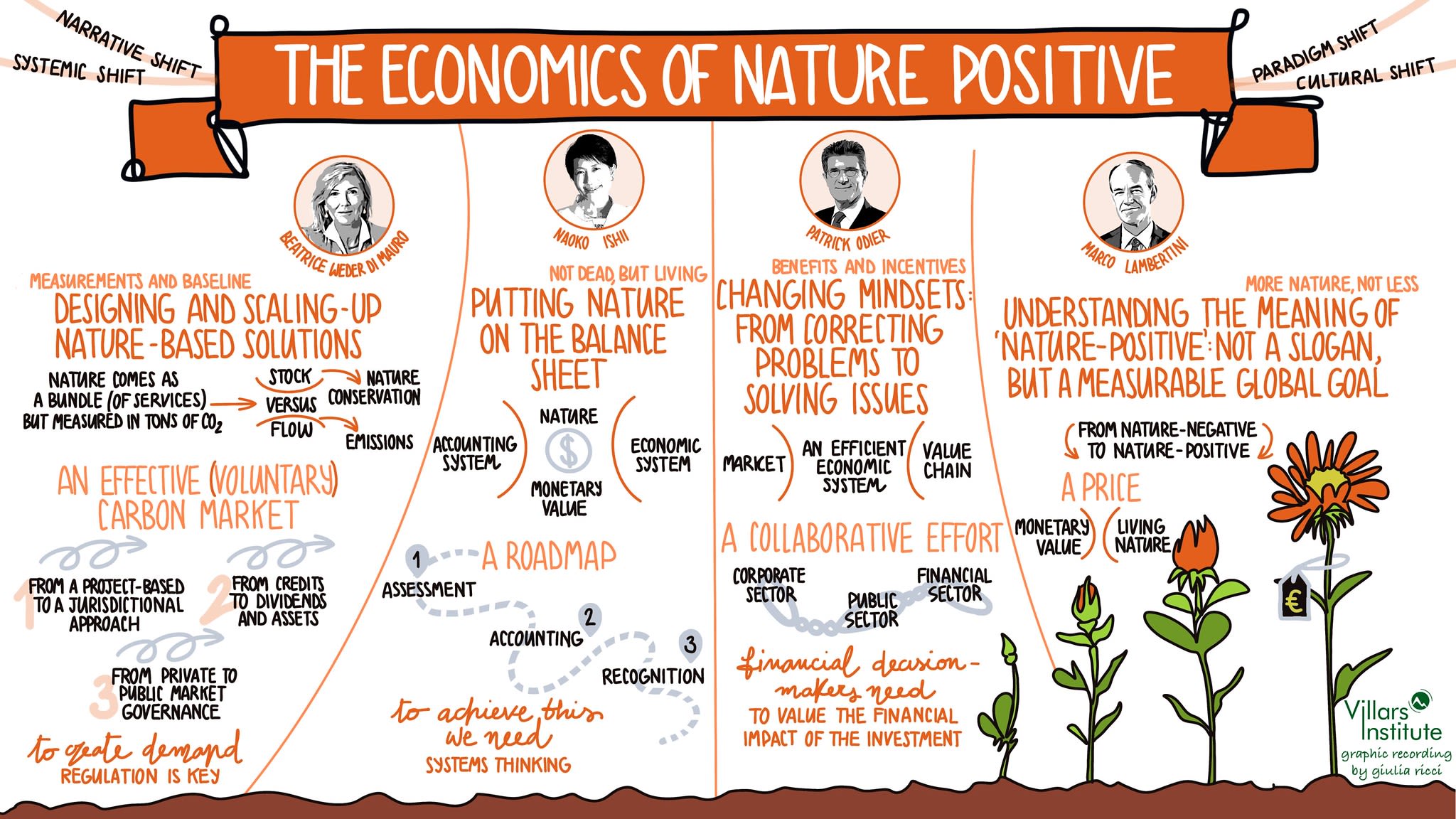

The session merged a discussion on the economic system with a philosophical reflection on our collective conscience. Three speakers provided innovative ideas on the complex but essential issue of transitioning towards a nature-positive economy. Their goal? Making the economic system beneficial for nature.

Nature positive by 2030 is, unfortunately, an immeasurable global goal. There is hope, however, because it goes hand in hand with the measurable goal of the climate agenda, as outlined in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. But measuring “more nature” is challenging when the baseline is centuries of degradation. Today’s economy not only fails to contribute to the improvement of nature but is also “nature negative”: we harm, and we don’t mind. Or so it seems. Natural capital is treated with the naive and dangerous assumption that it is infinite.

Nonetheless, the speakers proposed two plans that plant a seed of hope. The first expert highlighted that while we do care, what’s missing is a clear plan, and posed the question: How can we design markets that value nature without commodifying its essence? The speaker proposed to package nature's riches of services—forests, wetlands, and biodiversity—into tradable assets. A ton of CO2 is easy, as it becomes a commodity. But how do you assign value to a butterfly? High integrity markets make it difficult. However, the expert expressed confidence in moving away from predominantly project-based markets towards large-scale, jurisdictional approaches, and from private-market governance to primarily public governance. An effective conservation system will need to estimate what would happen without intervention to set a price, supported by regulations that help generate demand.

The second expert proposed a fresh idea that emerged during the breaks at the Villars Institute Summit 2024, namely, putting nature on the balance sheet. The expert’s clear plan is first to conduct a natural capital assessment, which entails discovering value based on trusted data. Natural capital accounting then allows quantifying the value to business and society. Fortunately, some progress has already been made, but there is a pressing need to integrate it into our economic system. Natural capital is then finally recognized in financial accounting, integrating it into business and sovereign decisions. The speaker emphasized that this clearly breaches planetary boundaries and stressed that our accounting systems need to catch up with ecological realities, so it’s time for us to change the system.

The third expert stated there is not only an economic gap but also a gap in mindset. The purpose of any economic system is to use the ingredients in a more efficient way. To achieve more effective funding, we cannot rely solely on a financial perspective but also need collaboration from the public sector for regulatory issues and local public policies, as well as active involvement from the commercial sector. This will support decision-making by establishing accounting regulations that reflect nature on the balance sheet. Investing in and funding nature will require a fundamental shift in mindset.

Insights from the Audience

The insights and discussions among participants reflected both the complexities and opportunities inherent in transitioning to a nature-positive economy. While the economic case for valuing natural assets is becoming increasingly compelling, significant challenges remain in operationalizing these concepts within existing financial structures.

A participant requested further elaboration on how to establish universally accepted frameworks that could integrate biodiversity and ecosystem services into economic decision-making. While natural capital accounting is emerging as a potential solution, concerns were raised about the reliability and consistency of data sources, as well as the challenge of creating financial instruments that accurately reflect ecological value over time.

Another key insight concerned the role of incentives and market mechanisms. Although the session reflected the consensus that voluntary action alone is insufficient, participants nonetheless debated the most effective ways to catalyze large-scale investments in nature in the near future. A few voiced concern that current mechanisms, such as carbon credits, have struggled with credibility, and questioned whether biodiversity markets would face similar pitfalls. The importance of ensuring transparency, integrity, and long-term investor confidence was stressed as a crucial priority.

The audience was cautiously optimistic as the discussion drew to a close. Both participants and panelists inquired about the importance of shifting from theoretical discussions to concrete implementation and paying particular attention to actionable roadmaps that bridge the gap between ecological science and economic strategy. An overarching sentiment emerged: to secure a truly nature-positive future requires a fundamental transformation of financial and corporate systems, one that no longer views nature as a mere externality, but recognizes it as a core asset essential to long-term prosperity.