At the Villars Summit 2025, Dr. Magdalena Skipper was invited to deliver the 5th Villars Institute Distinguished Lecture.

She shared profound perspectives, grounded in her leadership at the forefront of science, on what it takes for research ecosystems to flourish and why that is essential for addressing humanity’s greatest challenges, highlighting the seven defining qualities that will shape the future of science and our shared future on Earth.

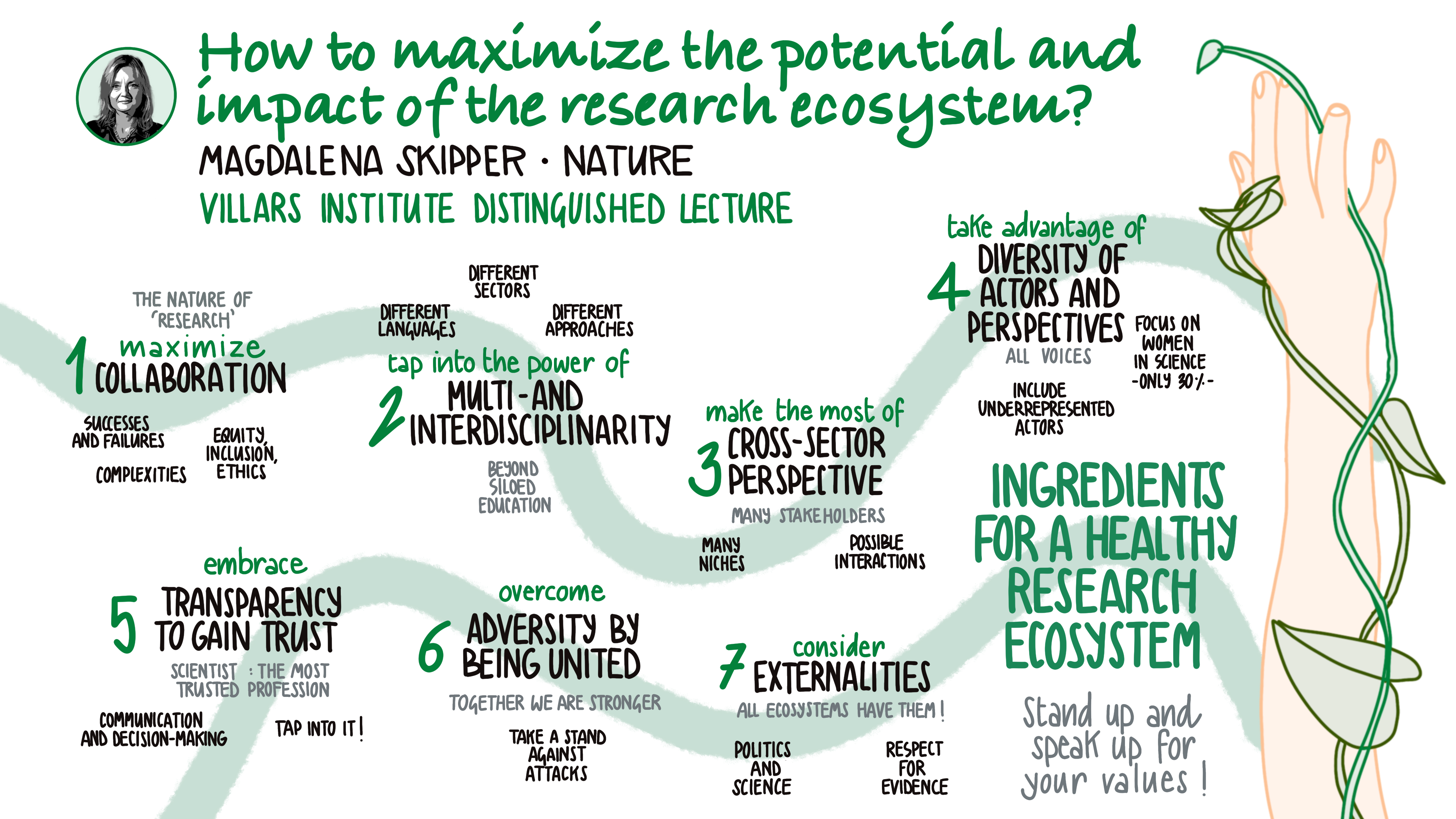

The 7 Qualities of Healthy Research Ecosystems

When scientific research ecosystems flourish, the Earth stands to benefit. But as Nature editor-in-chief Magdalena Skipper told the Villars Summit Distinguished Lecture, these communities all need some key ingredients to help them thrive…

Sometimes the most seismic scientific discoveries aren’t triumphant, punch-the-air “eureka” moments, but more the realization that humanity is teetering on a path towards self-destruction.

That was probably the case in 1985 when three British scientists discovered a gaping hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica, suspecting manmade chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – then widely-used in fridges, air-conditioning units and aerosols – were the guilty offenders.

What happened next was truly remarkable, testament to how some of the world’s most pressing problems can be solved with international research cooperation, and politicians taking warnings from scientists seriously.

Just two years later, 197 countries signed the Montreal protocol, agreeing to stop producing ozone-depleting substances. Today, 99% of these gases have been phased out, while projections from the United Nations Environment Programme indicate the Antarctic ozone layer is on track to be healed by 2066. The epochal discovery has also changed the way we live, from using sun protection creams to enhanced skin cancer awareness. Recent modelling by scientists found that if the Montreal protocol had never been signed, the rapidly-thinning ozone layer could have caused 2.5C of extra warming by 2100.

The world first found out its protective umbrella was being abused in a landmark paper which appeared in UK science journal Nature in May 1985. Since its first issue in 1869, Nature has published similar momentous scientific findings: James Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron in 1932, Watson and Crick unearthing the secret of life by determining the structure of DNA in 1953, Dolly the sheep (aka the first mammal to be cloned) in 1996.

At a time when scientific institutions and research communities are threatened by political cuts and rhetoric in many parts of the world, Nature editor-in-chief Magdalena Skipper delivered the fifth Villars Institute Distinguished Lecture, where she spoke about why healthy research ecosystems are essential if our planet has any hope of combatting the climate challenges that lie ahead.

She also identified the following seven qualities shared by flourishing research ecosystems:

1. Scientific successes mostly come from collaboration

As much as the public view of a scientist is of a ‘lone genius’ most scientific breakthroughs occur through teamwork and partnerships. The sequencing of the human genome (first published in Nature in 2001), for example, involved 20 separate universities/research institutions in five countries, hefty funding (estimated to be $3bn) and a timespan of 13 years. Thousands of scientists and researchers also worked together to discover the existence of the elusive Higgs boson particle in 2012; in early-2020 Covid prompted an unprecedented wave of global scientific collaboration which swiftly led to the sequencing of the coronavirus genomes and the production of vaccines within just one year.

“Research is collaborative by its very nature… you can’t imagine doing particle physics on your own,” says Skipper, who adds most papers published in Nature are multi-authored. “Many questions we’re all interested in answering today can only be addressed as a result of collaborative effort.”

However, collaboration comes with a caveat, with Skipper noting, “It’s not easy to collaborate effectively in a way that the perspectives of all collaborators are equally heard and acknowledged.”

This is particularly true of the practice of ‘helicopter science’ (or ‘parachute science’), which sees researchers from wealthy countries conduct research in poorer parts of the world (usually the global south) with limited or no participation from local communities and researchers. One 2020 report found two-thirds of high-impact geoscience articles on Africa had no African authors.

In 2022 Nature introduced an editorial framework to help safeguard against helicopter science, encouraging scientists/researchers to collaborate in a more ethical way, by providing disclosure statements, giving full credits on papers to researchers employed overseas and following the recommendations of the Global Code of Conduct for Research in Resource-Poor Settings.

2. The most effective collaborations are multi- or interdisciplinary

Both multidisciplinary research (which sees researchers from different disciplines working together, such as a quantum mathematician and molecular geneticist) and interdisciplinary research (which integrates expertise and perspectives from different disciplines) is seen as being integral to a fecund research ecosystem, with the synergetic coming together of different minds from varied backgrounds more likely to solve complex problems.

Nature is a prime example. As Skipper told the Villars Summit, Nature has been a multidisciplinary journal since it founded 156 years ago, publishing articles from social sciences such as psychology and anthropology, as well as natural sciences such as physics and chemistry. However, in recent years, Nature has helped broker interdisciplinary alliances between professions as wide-ranging as water engineering and town planning via the launch of thematic journals such as Nature Cities and Nature Chemical Engineering.

Multi- and interdisciplinary collaboration can be fraught with difficulties, however, such as funding issues or semantic differences.

“With different users of language, it’s not always clear what your [fellow] collaborators are talking about,” says Skipper. “Even if you’re using the same terminology, it might have different meanings. Sometimes the methodology is different [such as when] a natural scientist collaborates with a social scientist.”

The traditional siloed and compartmentalized way in which many university departments are run also presents a disciplinary dilemma, with Skipper noting these monolithic structures can prevent multidisciplinary research from thriving, making it harder for researchers to push boundaries.

3. Cross-sector collaboration can supercharge research goals

Today, most scientific research doesn’t solely involve scientists and academics, but is rather a heterogeneous symbiosis of different stakeholders: financiers, philanthropists, multinational corporations, pharma firms, charities, NGOs, even politicians.

In other words, to truly optimize the potential of a research project, forging alliances with other sectors is essential, leading to more jobs, plus the sharing of ideas and expertise. It can also unlock much-needed financial backing from sources outside the public sector: crucial at a time when national governments are slashing budgets for scientific research.

“The last few months have shown that we can’t rely on some governments to provide funding [for science],” says Skipper. “But there are other important sources of funding [which] will empower us to think creatively about how it can support other types of research… By collectively leveraging these different opportunities, we [science] will be stronger, our research will be better-suited and more appropriate to the questions we want to answer.”

4. A diverse research ecosystem helps science address problems more effectively

The global scientific research industry is beset by significant gender gaps and racial disparities. Data from UNESCO has shown that globally, women make up just one third (33.3%) of researchers, with the lowest densities in OECD countries.

“As we know from corporate research, those companies with diverse teams solve problems more effectively and provide more robust solutions [McKinsey has found those companies with better gender/ethnic representation have a 39% likelihood of outperforming their less-diverse peers],” says Skipper. “But if we want to maximize the health of the research ecosystem, are we really maximizing the opportunities of all these voices to be represented in the research? My proposition is we could be doing much, much better.”

Ensuring the research ecosystem is intergenerational is also crucial, especially in areas such as climate science. “The problems we’re facing today are multi-generational, so they need solutions to come from different generations,” says Skipper.

5. To build greater trust with the public, transparency is key

Every year, the Edelman Trust Barometer asks respondents in dozens of countries to find the world’s most trusted profession. For the past few years, there’s been an unexpected victor: scientist (trusted by 77% of people according to the 2025 survey). At the same time, trust in institutions and experts is hitting a nadir: people are more likely to trust their peers (more than the media) for information on new innovations, according to the 2024 Edelman Trust Barometer.

As Skipper points out, these shifts in public attitude represent a huge opportunity for science – which research ecosystems are failing to leverage.

“In other words, people are trusting those that look like them – which is good news for science because there are many members of the research ecosystem that look like the next person,” says Skipper. “Why wouldn’t we use that to communicate facts are an important basis for decision-making? We should be harnessing this.”

However, as the Villars Summit also highlighted, conveying findings about complex issues such as climate science is a perennial problem for scientists. To reach out to the public and gain their trust, scientists may need to exercise greater transparency.

This was seen during the pandemic, when those governments with the highest approval ratings were in countries such as New Zealand and Scotland, where epidemiologists admitted they didn’t know the answers about how this mystery coronavirus was transmitted, or its long-term symptoms. Paradoxically, people didn’t panic, but the transparency made them trust their leaders even more, resulting in greater adherence to public health measures.

“Scientists could do some help with how to communicate, [communicating/expressing] what gets them out of bed in the morning,” says Skipper. “We could be losing something by not tapping into this level of trust they have.”

6. Political skepticism towards science and facts is at a high: it’s time for scientists to take a stance

In October 2024 Nature published an editorial one week before the US election, headlined, “The world needs a US president who respects evidence”, arguing Donald Trump’s climate change denial and relentless undermining of scientific institutions could disrupt global politics by “giving the green light to yet more leaders like him”.

Six months later, the US is the only country to have withdrawn from the Paris climate agreement, while Trump has employed radical science-deniers in his government, plus cast the future of research into doubt by slashing funding and jobs. Similar assaults on science have been happening in Argentina (the country’s main science agency has undergone a ‘scienticide’ under president Javier Milei, losing 9% of its workforce).

“If leaders don’t respect facts or evidence, then we’re all in trouble,” says Skipper, who also referenced Galileo – the Italian astronomer/physicist who was tried by the Roman Inquisition in 1633 for suggesting the Earth went around the sun.

As some governments seek to discredit their profession, scientists shouldn’t retreat into their ivory towers, but work with politicians, says Skipper. After all, if the world wishes to combat the next pandemic, find drugs to cure cancers or develop sustainable fuels in the race to net-zero, then scientists will be needed.

“In my view, scientists shouldn’t shy away,” she says. “The magnitude of what’s happening in the US is unprecedented in recent times… I’d suggest that we, as a community and ecosystem, should come together, stand up for our values and our conviction that facts are the foundations to all the solutions we’re trying to build towards.”

7. In science, progress never ends…

Whether it’s mRNA technology being used to develop cancer vaccines, or the James Webb telescope photographing the most distant known galaxy, the research ecosystem is currently underpinning some of the most promising innovations in science.

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) is set to transform the world of scientific research too: professor Mark Thomson [CERN’s next director-general] recently suggested AI will hugely advance particle physics, perhaps even revealing how the universe might end.

“I think we’ll see an increasing amount of research being generated in an AI-assisted way,” says Skipper. “Hypotheses and data training are already being generated with AI tools. AI is also exceedingly good at analyzing image data, and environmental monitoring… But we need to pay more attention to making AI less energy-hungry [research suggests 700,000 liters of water could have been used to cool the machines that trained ChatGPT-3].”

The research ecosystem could also expand to welcome the rise of ‘citizen science’, says Skipper. Harnessing the enthusiasm and curiosity of passionate amateurs is a trend that’s been embraced most emphatically in astronomy: the European Space Agency recently partnered with citizen science project Galaxy Zoo to enlist the help of volunteers in classifying tens of thousands of galaxies. Meanwhile, in the UK, over 7,000 people took part in NGO Earthwatch Europe’s campaigns (or ‘WaterBlitzes’) last year to test river water quality for phosphates, nitrates and other pollutants.

In the years ahead, the seven qualities identified by Skipper will be critical not just for fostering healthy research ecosystems, but for anybody interested in confronting some of the most urgent challenges of our time. There’s also much crossover with the type of systems leadership espoused by the Villars Institute, as well as its notions of interdisciplinary and intergenerational collaboration.

“Let’s take advantage of the diversity of perspective and voices – it’ll make science better, make our solutions better,” says Skipper. “Not only will the answers be more complete, but they’ll be easier to implement too. We must embrace transparency to gain trust and fight misinformation, and the adversities that come from some governments. Let’s be united in how we face these adversities together. And let’s speak up and be present on the global stage too.”